By Esther Stanford-Xosei*

A version of this article was published on Self-Help News on the 30th November 2021. Uhuru means freedom in Kiswahili.

On 30th November 2021, Barbados transitioned from a parliamentary constitutional monarchy under the hereditary monarch of Barbados (formerly Queen Elizabeth II) to a parliamentary republic with a ceremonial non-executive President as Head of State elected by members of parliament and not the people. The Prime Minister, Mia Mottley EGH, OR, QC, MP remains Head of Government.

However, the question that I and many other citizens of Barbados have been discussing is whether this transition to a republic is more symbolic rather than substantive. Whilst much of the corporate whitestream media is hailing this move as some huge achievement, questions remain about whether selecting the existing Governor-General, Dame Sandra Mason GCMG, DA, QC, who had been Queen Elizabeth’s II’s representative in Barbados since 2018, to serve as Barbados’s first President and Head of State is really the kind of substantive change one would expect when a country transitions to a republic. Queen Elizabeth II bestowed on Mason the Dame Grand Cross in the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George when Mason was appointed Governor-General.

Lest we not forget, the hitherto Governor-Generals of Barbados are appointed by Queen Elizabeth II supposedly on the advice of the Prime Minister of Barbados. Nevertheless, the fact that two thirds of the Barbados Parliament selected the (former) Governor-General to become the first President of the Republic of Barbados could be seen as an attempt to hoodwink the people into believing that there has been a changing of the power structure, when that is clearly not the case. Indeed, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Any new president of a republic, should be directly elected by the people of Barbados.- a point that was made months ago by Dr Ronnie Yearwood, a law lecturer at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus who has cautioned against a: “president formed in the backrooms of the Parliament functioning as an electoral college for choosing a president, likely one of the same political class.”

Significantly, Following the end of the Dame Sandra Mason’s term as president, future presidents will be elected by either a joint nomination of the Prime Minister and leader of the opposition or if there is no joint nomination, a vote of both houses of the Parliament of Barbados where a two-thirds majority is required. The electorate will therefore have no meaningful say. As Opposition Senator, Caswell Franklyn has also argued, there are flaws in the republic process. To raise legitimate concerns about the manner in which Barbados is transitioning to a republic does not mean that one is against republicanism, this is indeed long overdue. Nevertheless, it is prudent to raise the fact that the process we are embarking on in Barbados appears to be more symbolic rather than substantive. It reminds me of when President Obama became President of the United States and people got caught up with him being reported to have been the so-called first Black President of America (which was not true), rather than looking at how his presidency impacted on people of Afrikan ancestry and heritage.

Many are also getting caught up with the symbol of a first President of Barbados who also is a woman rather than critically examining the substance of how meaningful these changes will be. Whenever it comes to women in power and the tendency to see women in positions of (neocolonial) state power as emancipatory, I always question to what degree such women are or act, in ways that is described by Dr June Terpstra, as Women of the Hegemon. To find out more about what this means see here and here. In a global system of imperialism and neocolonialism, the Hegemon is ever-present even when it may be difficult to see because of the tendency to use a single lens of analysis when assessing reality rather than embracing an analysis of power on intersectional grounds.

I like many other agree that we should have a new constitution fit for purpose of what it means to be a republic drafted with input from our people who have up until now not really been given a say about what type of republic they want Barbados to be. Only then could it be said that there is a fair and equitable process which reflects a real intention to break with the coloniality of power of ‘Global Britain‘. Instead, Barbados’ republic status is premised on retaining links with European coloniality by simply making amendments to a constitution that came out of the Barbados Independence Act of 1966 passed by the UK Parliament, which gave Barbados “fully responsible status” (independence) within the Commonwealth. This Act has not been repealed.

According to the UK House of Commons Library Section 5 of that Act allowed Queen Elizabeth II, by Order in Council to:

“…provide a constitution for Barbados. This took the form of the Barbados Independence Order 1966, which was laid before the Barbados Parliament on 22 November 1966 and came into force on 30 November. The Constitution of Barbados formed a schedule to that order. This was drafted by a Constitutional Conference comprising political parties in Barbados and the then UK Secretary of State for the Colonies.”

In a recent article Dr Yearood & Professor Cynthia Barrow-Giles opined:

“….Barbados will move inexorably to republican status but with the status quo remaining, and with the symbolic change associated with the national head of state both practically and theoretically representing the citizens and not theoretically a foreign head of state. The real issue is therefore not about whether Barbados becomes a republic, or whether the Constitution is patriated, but about the relationship between the people and the Government as articulated in the Constitution. Is Barbados going to change its Constitution or be content with tinkering around the edges, masquerading as change?“

It would be far more transformatory, if an entirely new constitution was drafted instead of trying to seemingly ‘repair’ this colonial Westminster instrument. There is a long-standing need for constitutional review and reform which enables the electorate to have a greater degree of participation in accountable governance of the country. In order to become a republic, the Barbados Parliament had to revoke the Barbados Independence Order 1966 as an Order in Queen Elizabeth II’s Council via the Constitution (Amendment Bill) 2021, while keeping intact the existing Barbados Constitution. The amendment transfers the functions and powers of the Barbados Governor-General (Queen Elizabeth II’s representative) to the new President of the republic, amending the official oaths of Barbados to remove references to the Queen Elizabath II, as well as ensures continuity in all of the other aspects of the functioning of the state of Barbados.

The UK Parliament will have to pass consequential legislation “to avoid any confusion in its domestic law” as has been the case on previous occasions when Commonwealth Realms have become republics. The last time ithe UK Parliament passed a similar bill was the Mauritius Republic Act 1992. It is this aspect of the process thus far to republicanism that is most indicative that for now, Barbados will become a republic in name only. When a nation is seeking to establish true independence on the road to sovereignty, it cannot do so by maintaining relics of the colonial power that has ruled and influenced its institutions of governance for centuries. No wonder Prince Charles was invited as a guest of honour to make an address at the ceremony marking Barbados’ transition to a republic.

The cockily confident, Prince Charles felt it necessary in his public messaging on behalf of Queen Elizabeth II to emphasize those things “which will not change” such as the: “close and trusted partnership between Barbados and the United Kingdom”, the “common determination to defend the values we both cherish and to pursue the goals we share; and the myriad connections between the people of our countries.” He was even awarded the Order of Freedom of Barbados, which is now the country’s highest distinction. Quite rightly, the contradictions inherent in this decision has been condemned. In a recent facebook post Dr Tyehimba Salandy, a sociologist and scholar-activist based in Trinidad & Tobago says: “There is something very problematic about proclaiming Republic status and at the same time instead of pressing home the case for reparations awarding the creators of some of the worst crimes ever in human history with the Order of Freedom.”

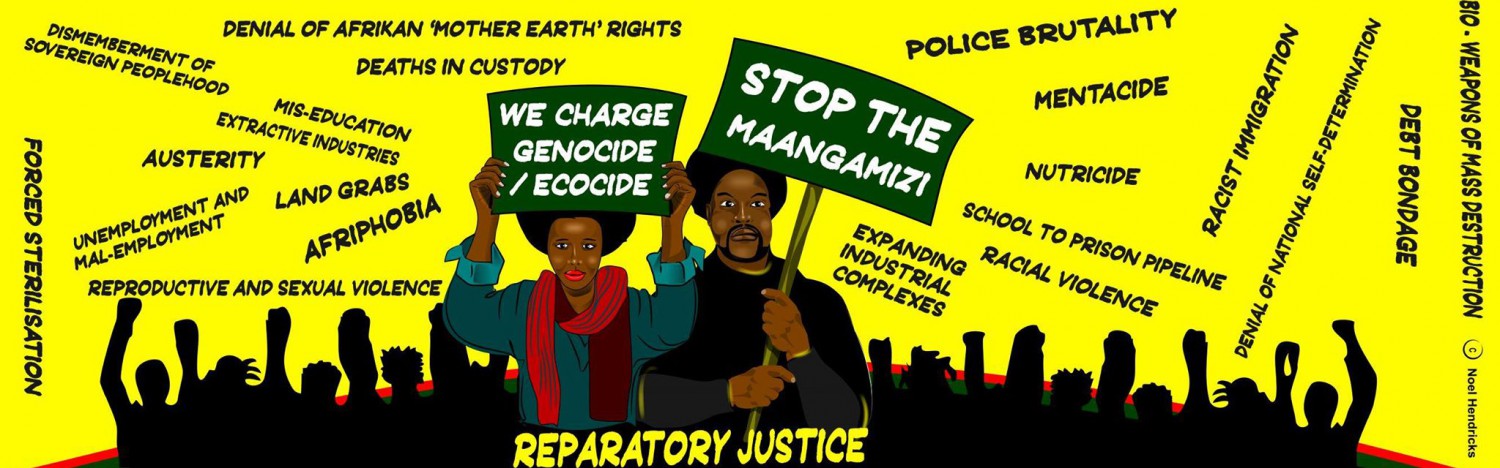

Not surprisingly, Prince Charles’ visit has generated condemnation from across civil society, campaigners from the Caribbean Movement for Peace and Integration and the 13th June 1980 Movement had planned to stage a protest in Bridgetown, the capital of Barbados yesterday. However, the government refused to grant permission for the protest. Clearly, such campaigners in Barbados, need support in amplifying their voices especially in the UK to present a counter narrative to this celebratory tone which is smothering those voices who are challenging the dominant state approaches to republicanism which are obfuscating the most fundamental issues of Global Europe and the continuance of Afrikan powerlessness in the Caribbean and elsewhere around the world. That is why the UK contingent of the International Social Movement for Afrikan Reparations campaign, driven by the Stop The Maangamizi: We Charge Genocide/Ecocide Campaign, to establish a UK All-Party Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry for Truth & Reparatory Justice which prompted the establishment of the UK All-Parliamentary Group on Afrikan Reparations (APPGAR), will become of increasing importance in this regard.

The Secretary General of the Caribbean Movement for Peace and Integration, David Denny is right to say that Prince Charles’ visit is an insult! According to a recent report in the Daily Mirror: David Denny who felt the opportunity should be used to call for an apology and reparations, said:

“Barbados should not honour a family who murdered and tortured our people during slavery. The profits created the financial conditions for the Royal Family to increase their power.”

Kevin Cahill provides good justification of this last point when he uncovers in his 2007 book: ‘Who Owns the World’, the world’s primary feudal landowner remains Queen Elizabeth II. She is monarch of 15 countries in addition to the United Kingdom, head of a Commonwealth of 54 countries in which a quarter of the world’s population lives and holds legalised title to about 6.6 billion acres of land, one-sixth of the earth’s land surface.

Wherever one stands on this issue, deeper questions remain; like how will the centuries old accumulated benefits acquired by the British Monarchy be dismantled in Barbados? What will the rulership do to free the country of imperial influences, the Maangamizi of neocolonialism and its attendant neoliberal economic reforms?, which are not only raising the cost of living for ordinary people and exacerbating income inequality; but also furthering the dominant model of maldevelopment worldwide which has implications for effectively tackling the genocidal and ecocidal glocal impacts of the worldwide Climate and Ecological Crises and the necessity for charting alternative paths of progression in Barbados premised on transformtaive adapatation as an aspect of Planet Repairs. Will there be widespread land, wealth and resource redistribution?, especially since (prior to becoming a republic) the British Monarch owned all state lands and state-owned companies etc. I really doubt it!

Despite becoming a Republic, Barbados remains one of the most important offshore financial centres in the Caribbean and one of the world’s top 15 according to Oxfam. Accordingly, there is a link between financialisation and the growth of top incomes. In an article written whilst he was a PhD researcher at the London School of Economics, Scholar Dr Collin Constantine argues that: “Barbados’ status as an offshore financial centre also contributes to rising inequality in Western Europe and the USA by allowing wealthy foreigners to shift income and wealth into a low-tax jurisdiction. Yet while OECD countries are attempting to reclaim their “hidden wealth”, Bajans face growing inequality alongside austerity measures and weak tourism.” Constantine provides an important perspective on how the ‘idea’ of Barbados as a beacon of democracy in the Caribbean persists. He argues that this is in part the same issue studied in other contexts by Thomas Piketty: “When you have large wealth, you cannot just consume like other people. You start to consume influence, consume politicians, consume academics, you consume power; this is what high wealth is here for.”

Constantine goes on to state: The enormous concentration of income in Barbados historically meant that the most powerful and prestigious positions were reserved for colonial elites. In present-day Barbados, economic elites use grants, media ownership, campaign contributions, and so on to influence public policy, public opinion, and key actors to forge societal buy-in on policies that protect and reinforce elites’ economic interests. Even more than in OECD countries, part of the problem is a lack of transparency about top incomes in Barbados, with a severe lack of studies on wealth and income distribution. But this is compounded by deliberate attempts to shift the blame onto the most visible participants in the local economy, namely migrants.

The above arguments put forward by various commentators demonstrate that there is still a long way to go before we can say that we have overcome the tyranny of gradualism and effected as well as secured Uhuru in Barbados and across the Caribbean region. The struggle to transform our material, spiritual and cultural realities naturally leads to the path less travelled; i.e. that of continuing to build and strengthen movement-building for Pan-Afrikan Liberation at home in our Motherland Afrika, as well as across the Diaspora. This is concretised by the Stop The Maangamizi Campaign’s advocacy of the necessity to prefigure decolonial post-Afrikan Reparations futures epitomised by the establishment of Maatubuntuman in Ubuntudunia built from the emerging Community Resistance Zones such as Maatubuntujamaas (Afrikan Heritage Communities for National Self-Determination) in the Diaspora, organically and indivisibly linked to Sankofahomes premised on our indigenous Afrikan Communities of Resistance throughout the Continent of Afrika.

As Pan-Afrikan Reparationist Kofi Mawuli Klu, my fellow co-vice chair in the Pan-Afrikan Reparations Coalition in Europe asserted in 1993:

“Unless our struggle for Reparations leads to the Pan-Afrikanist revolutionary consientization, organization and mobilization of the broad masses of Afrikan People throughout the Continent and the Diaspora to achieve first and foremost, their definitive emancipation from the impeding vestiges of colonialism and the still enslaving bonds of present-day Neocolonialism, to smash the yoke of white racist supremacy and utterly destroy the mental and physical stranglehold of Eurocentrism upon Afrikans at home and abroad, delinking Afrika completely from imperialism of any sort whatsoever, we shall have no POWER to back our claim for restitution and to give us the necessary force of coercion to make the perpetrators of the heinous crimes against us to honour the obligations of even the best fashioned letter and spirit of International Law.”

*Esther Stanford-Xosei is a Motherist and Pan-Afrikanist Jurisconsult, Community Advocate and Reparationist. As a ‘new abolitionist’ emphasizing the need to ‘stop the harm’ and effect Planet Repairs, Esther serves as the Coordinator-General of the Stop The Maangamizi: We Charge Genocide/Ecocide Campaign, among other responsibilities.