This text has kindly been updated and reproduced with permission from https://reparationsscholaractivist.wordpress.com/2013/09/20/overstanding-reparations/

Brief Survey of the Literature

Reparations as a concept is one of the most misunderstood terms with popular understandings of reparations associating it with financial compensation. It is important to look to how reparationists have defined the term. In a paper presented at the Birmingham Preparatory Reparation Conference, on 11th December 1993 organised by the African Reparations Movement (ARM, UK), Dr Kimani Nehusi[1] asserts that understanding the term reparations “demands that this notion be applied to the specific historical experience and the related contemporary condition of Africans” asserting that “the meaning of this term transcends repayment for past and continuing wrong, to embrace self-rehabilitation through education, organisation and mobilisation.”Nehusi goes on to highlight the etymology of the term ‘reparation’ which originates from Latin pointing out that there are a number of meanings associated with the term.

One of these lines of development being the modern English term repair meaning: to restore to good condition, to set right, or make amends concluding that the Modern English term ‘reparation’ speaks to: “the act, or instance of making amends; compensation.” Similarly, Waterhouse (2006) quoting from the Oxford English Dictionary points out that the concept of making amends is only one of two of the original meanings of repair and reparations, and that the other set of meanings are “to restore or renew.”[2] Waterhouse therefore concludes that reparations are best understood as efforts to repair past damages however, he also asserts that the broader meaning of repair, “relates to the transformation of the thing damaged,” best to be understood as meaning “its restoration or renewal.”

This notion of reparations as repairs has also been advanced by continental based Afrikan public intellectuals such as Nigerian Professor Chinweizu, who in his famous paper presented at the Abuja Conference ‘Reparations and New Global Order: A Comparative Overview’ defined reparations in this way:

“Let me begin by noting that reparation is not just about money: it is not even mostly about money; in fact, money is not even one percent of what reparation is about. Reparation is mostly about making repairs. self-made repairs, on ourselves: mental repairs, psychological repairs, cultural repairs, organisational repairs, social repairs, institutional repairs, technological repairs, economic repairs, political repairs, educational repairs, repairs of every type that we need in order to recreate and sustainable black societies….More important than any monies to be received; more fundamental than any lands to be recovered, is the opportunity the reparations campaign offers us for the rehabilitation of Black people, by Black people, for Black people; opportunities for the rehabilitation of our minds, our material condition, our collective reputation, our cultures, our memories, our self-respect, our religious, our political traditions and our family institutions; but first and foremost for the rehabilitation of our minds”.[3]

It can thus be concluded then popular conceptions of reparations within the International Social Movement for Afrikan Reparations (ISMAR) should be viewed as an obligation to make the repairs necessary to correct current harms caused as a result of past wrongs. Under this view, reparations can be viewed as a process that restores hope and dignity and rebuilds communities rather than being reduced to a pay check. This notion of ‘reparations as repairs’ has also been advocated by reparations legal and political theorists in the USA. For example, Yamamoto et. al (2007) advocate the ‘reparations as repair’ model to help elevate the role of reparations potential to “create social healing and generate practical theory” as well as ways of ”doing justice” that link scholars and front-line reparations advocates with legal policymakers and the [American] public.[4]

The right to reparation has also been recognised as a fundamental right and well established principle in international law which according to the human rights organisation REDRESS that helps torture survivors obtain justice and reparations “has existed for centuries” and refers to the obligation of a wrongdoing party to redress the damage caused to the injured party. [5] Typically in the 19th and 20th centuries, reparations came to be associated with punitive sanctions against aggressor states following their defeat in war. However, among the significant transformations of reparations politics in more recent times has been a shift from reparations involving states, to cases involving both states and civil society actors, who are usually racial or ethnic groups united by their common experience of a historical injustice.

Under international law, “reparation must, as far as possible, wipe out all the consequences of the illegal act and re-establish the situation which would, in all probability, have existed if that act had not been committed.”[6]In 2005, the UN General Assembly adopted the ‘Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Violations of International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law‘.[7] These principles go some way towards codifying the norms relating to the right to reparation and also dispel one of the most common misconceptions, i.e. that reparation is synonymous with compensation. Other forms of reparation contained in these norms include: restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition.Ultimately, reparations are meant to redress past wrongs, to stop and repair the harms inflicted, and to rehabilitate those who continue to suffer the consequences of these harms, what are referred to as the individual and collective victims in international law. With this in mind, it is always imperative to consider whether the means of reparation under consideration will effectively lead to the ends envisaged, including analysis of any consequences, (both positive and adverse), of such measures of reparations being proposed or advocated for.

Repatriation is not Separate from Reparations, but Rather an Aspect of Restitution: a Specific Form of Reparations

It is common in some circles to hear the term reparations and repatriation used as though they represent two different yet complimentary aspects of reparatory justice, when in in fact, repatriation is an aspect of reparations and would appropriately be a form of restitution arising from the Afrikan Diaspora’s collective exclusion from citizenship due to the Maangamizi which resulted in the deracination and loss of peoplehood, citizenship and right to belong to Afrika for people of Afrikan origin. After all, Afrikan people were kidnapped from Afrika and trafficked against our will to many parts of the Afrikan Diaspora. It follows that what is typically considered to be repatriation has to be seen as a legitimate way of redressing and repairing these original crimes. The right of return is a principle which is drawn from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), intended to enable people to return to, and re-enter, their country of origin. The UDHR article 13 states that “[e]veryone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each State. Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.” (emphasis added).

However, repatriation meaning a return to one’s patria or fatherland or the process of returning a person to their place of origin or citizenship is in itself not sufficient. Firstly, Afrikan people’s concept of Afrika being the Motherland is not the same as the Roman concept of patria. Afrika is recognised as being a Motherland, not a Fatherland because it is the birthplace of humanity, the cradle of human civilisation and culture. For a people in the process of reestablishing their National Self-Determination, repairing and restoring themselves, repatriation cannot be reduced to just a return to a particular country of origin or physical return. It must entail the re-establishment and creation of bonds between displaced Afrikans and Afrikans in the Motherland; a return to community and people, and the restoration of community and nationhood. It must also be remembered that this right to return is also a right of displaced and dispossessed Afrikan people on the Continent of Afrika.

In reclaiming the ‘Power to Define’, it must also be recognised that there can be ‘No True Reparations without Rematriation’. The Indigenous concept of Rematriation refers to restoring a living material culture to its rightful place on Mother Earth; restoring a people to a spiritual way of life, in sacred relationship with their ancestral lands; and reclaiming ancestral remains, spirituality, culture, knowledge and resources. In effect, rematriation requires, as anti-colonial leader Amilcar Cabral taught, a return to the source of a people’s own being; reaffirming Afrikan people’s right to take our own place in history; rejection of colonial and neocolonial structures, ideologies and worldviews of European imperialism and elitist Arab hegemonic national chauvinism and other foreign oligarchies in the process of building politically a mass based Afrikan cultural renaissance. Rematriation is vital because of the need for cognitive justice in framing indigenous Afrikan conceptualisations of reparations.

Classical and Indigenous Afrikan Approaches to Reparations

Dr Maulana Karenga, Professor of Africana Studies in his paper: ‘The Ethics of Reparations: Engaging the Holocaust of Enslavement’ asserts that reparations, like all our struggles, begins with the need for a clear conception of what we want, how we define the issue and explain it to the world and what is to be done to achieve it. [8]He puts forward the argument that the ethical dimension is the first and most fundamental dimension of the reparations issue. He teaches that in the Husia, the sacred text of ancient Egypt, there is an Afrikan concept of restoration, i.e., healing and repairing the world that is appropriate in discussing our struggle to advance the cause of reparations. This concept is serudj which is part of a phrase serudj-ta, which Karenga states means to repair and heal the world making it more beautiful and beneficial than it was before.

Accordingly, he asserts that this is an ongoing moral obligation in the Kawaida (Maatian) ethical tradition and is expressed in the following terms:

(1) to raise up that which is in ruins;

(2) to repair that which is damaged;

(3) to rejoin that which is severed;

(4) to replenish that which is depleted;

(5) to strengthen that which is weakened;

(6) to set right that which is wrong; and

(7) to make flourish that which is insecure and undeveloped.

Equally as relevant is the work of Mogobe B. Ramose, Professor of Philosophy who teaches on Afrikan conceptions of justice and race. In his paper ‘An African Perspective on Justice and Race‘, he argues that since it is no longer tenable to argue that the idea and practice of law was alien to the indigenous Afrikan peoples prior to colonisation, an essential aspect of repairing the damage of enslavement and colonisation is to reclaim Afrikan conceptions and frameworks of justice. [9]Quoting Kéba M’Baye, Ramose reminds us of the importance of working according to Afrikan conceptions of justice and seeking to gain recognition for Afrikan people’s rights to do so when he states: “A debt or a feud is never extinguished till the equilibrium has been restored, even if several generations elapse … to the African there is nothing so incomprehensible or unjust in our system of law as the Statute of Limitations, and they always resent a refusal on our part to arbitrate in a suit on the grounds that it is too old”.

Thus in the ubuntu understanding of law, an injustice that endures in the historic memory of the harmed is never erased merely because of the passage of time. The work of former N’COBRA Legal Consultant and Ajunct Professor of Law, Adjoa Aiyetoro is relevant here. In her article ‘Formulating Reparations Litigation through the Eyes of the Movement’ she advocates that: “In order for people who have been shut out of the system to obtain meaningful remedies for violations of their human rights, redefinition of some ordinary and some uncommon terms must be accepted by the legal system”.[10]

Reparations for What?

Reparations is not just a legal case or a political claim but also a social movement. In ‘An Approach to Reparations‘ Human Rights Watch maintain that “when addressing relatively old wrongs, claims of reparations should not be based on the past abuses of enslavement and colonisation solely, but on its contemporary effects.”[11] They point out that people today, i.e. the descendants of the enslaved who can reasonably claim that today they personally suffer the effects of past human rights violations through continuing economic or social deprivation are deserving of reparations.

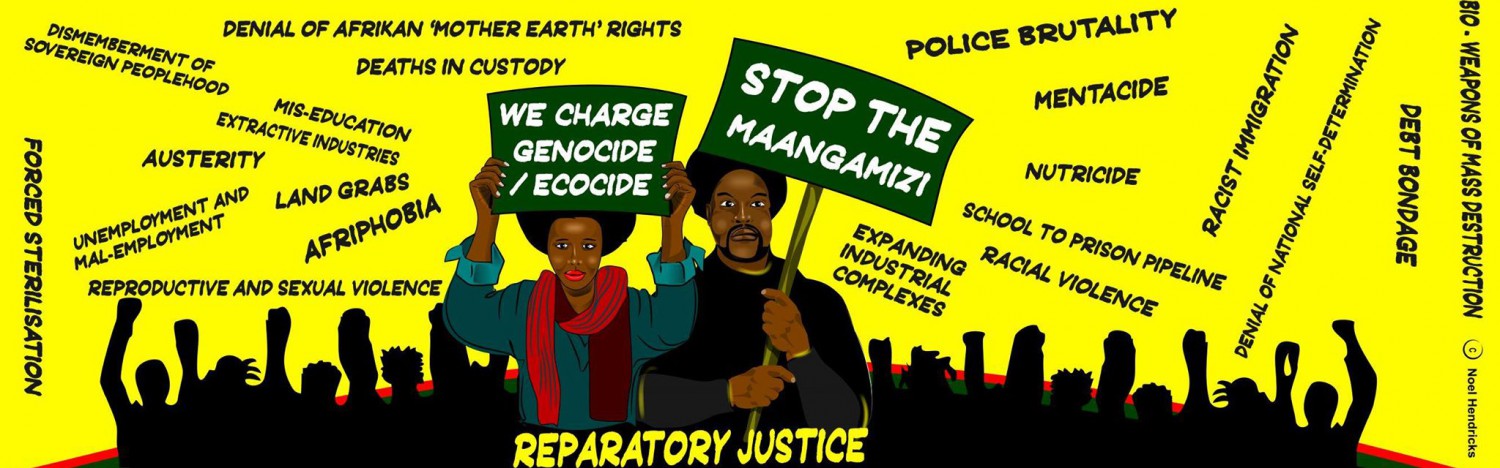

There is great potential in utilising the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crime of Genocide as an advocacy tool. In his book ‘Never Meant to Survive: Genocide and Utopias in Black Diaspora Communities‘, Joao H. Vargas, Associate Professor of African American Studies and Anthropology establishes that the relentless and intergenerational oppression and marginalisation of large numbers of Black people in modern societies constitutes genocide, in that groups among us are subjected to conditions of life that are sufficiently destructive to amount to instances of genocide. In this regard, it is important to also understand indirect genocide (which involves creating life conditions which destroy a group and facilitate intra-community violence).

According to Raphael Lemkin, the Polish-Jewish lawyer who coined the term genocide, genocide has two phases: one, the destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor. [12] In the 1948 Genocide Convention, genocide is therefore defined as follows:

“Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Vargas poses the following challenge:

“We either begin to address, redress, and do away with what make possible the multiple facets of anti Black genocide, or we succumb to the dehumanising values that produce and become reproduced by the systematic and persistent disregard for the lives of Afro-descended individuals and their communities.”[13]

It is important to therefore recognise however, that there are two dimensions to reparations, the external and the internal. The external is what we say others owe us but the internal self repairs are what we must engage in by way of restoring our agency, and asserting our right to self-determination and dignity as people of Afrikan heritage. Many Afrikans in Afrika and other parts of the Afrikan Diaspora are asserting the highest form of reparations as being a restoration of our sovereignty and the need to forge Pan-Afrikan Sovereignty which never ceded and has never been restored since Afrika was colonised. Independence and sovereignty are not the same things! There are two main ideological tendencies, that which has been associated with various forms of Afrikan/ Black nationalisms and linked to the restitution of land, language, culture, community, nation and Pan-Afrikan citizenship. The other dominant tendency has been the integrationist approach which sees reparations as being about Afrikans gaining more fulfilling experiences of citizenship within the West and more successful integration of Afrikans within Euro-American nations.

The question is can reparations truly occur if we are simply seeking to emulate our former colonisers, do we not owe it to ourselves to (as Frantz Fanon admonished us many years ago):

I close with the words of Professor Chinweizu:

“Now, we who are campaigning for reparations cannot hope to change the world without changing ourselves. We cannot hope to change the world without changing our ways of seeing the world, our ways of thinking about the world, our ways of organising our world, our ways of working and dreaming in our world. All these, and more, must change for the better. The type of Black Man and Black woman that was made by the holocaust – that was made to feel inferior by slavery and then was steeped in colonial attitudes and values – that type of Black will not be able to bring the post-reparation global order into being without changing profoundly in the process that has begun; that type of Black will not be even appropriate for the post-reparation global order unless thoroughly and suitably reconstructed. So, reparation, like charity, must begin with ourselves…”.[15]

________________________________________

[1] K. Nehusi (1993) ‘The Meaning of Reparation’ unpublished paper presented at the First UK Preparatory Conference on Reparations, (1993)

[2] C. Waterhouse, ‘The Full Price of Freedom: African Americans Shared Responsibility to Repair the Harms of Slavery and Segregation’, Graduate School of Emory University PhD thesis, (2006), p3.

[3]Presented at the ‘First Conference on Reparations for Slavery, Colonialism and Neo-colonialism’ which took place in Nigeria in 1993.

[4] E.K Yamamoto, E.K,, S. Hye Yun Kim, S. and A.M Holden, A.M ‘American Reparations Theory and Practice at the Crossroads,’ California Western Law Review, Vol.44, No.1. (2007).

[5] REDRESS, ‘What is Reparation’ http://www.redress.org/what-is-reparation/what-is-reparation

[6] See Permanent Court of Arbitration, Chorzow Factory Case (Ger. V. Pol.), (1928) P.C.I.J., Sr. A, No.17, at 47 (September 13); International Court of Justice: Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. U.S.).

[7] ‘Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparations for Victims of Gross Violations of international Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Law’, United Nations General Assembly Resolution 60/147, 21 March 2006.

[8] Presented at The National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA) Convention, Baton Rouge, LA, 2001 June 22-23

[9] http://them.polylog.org/3/frm-en.htm

[10] http://law.nyu.edu/ecm_dlv2/groups/public/@nyu_law_website__journals__annual_survey_of_american_law/documents/documents/ecm_pro_065061.pdf

[11] http://www.hrw.org/legacy/campaigns/race/reparations.htm

[12] Raphael Lemkin, ‘Axis Rule in Occupied Europe’ (1944)

[13] J.H. Vargas Never Meant to Survive: Genocide and Utopias in Black Diaspora Communities (New York, Toronto, Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008), p.x

[14] Frantz Fanon,’The Wretched of the Earth’, Chapter 6. Conclusion (1961)

[15] http://www.ncobra.org/resources/pdf/Chinweizu-ReparationsandANewGlobalOrder1.pdf